The Plain

[Fortress West Point]

SIGNIFICANCE:

Although not formally known as “The Plain” as it is today at West Point, the naturally occurring geography created the ideal cantonment and training area for Revolutionary soldiers. In 1778, First Lieutenant Samuel Richards, who as the senior officer present marched the 3rd Connecticut Regiment over the ice from Constitution Island to West Point on 27 January, recalled years later what the soldiers first saw: “Coming on to the small plain surrounded by high mountains, we found it covered with a growth of yellow pines ten or fifteen feet high; no house or improvement on it, the snow waist high. We fell to lopping down the tops of shrub pines and treading down the snow, spread our blankets, and lodged in that condition the first and second nights.”

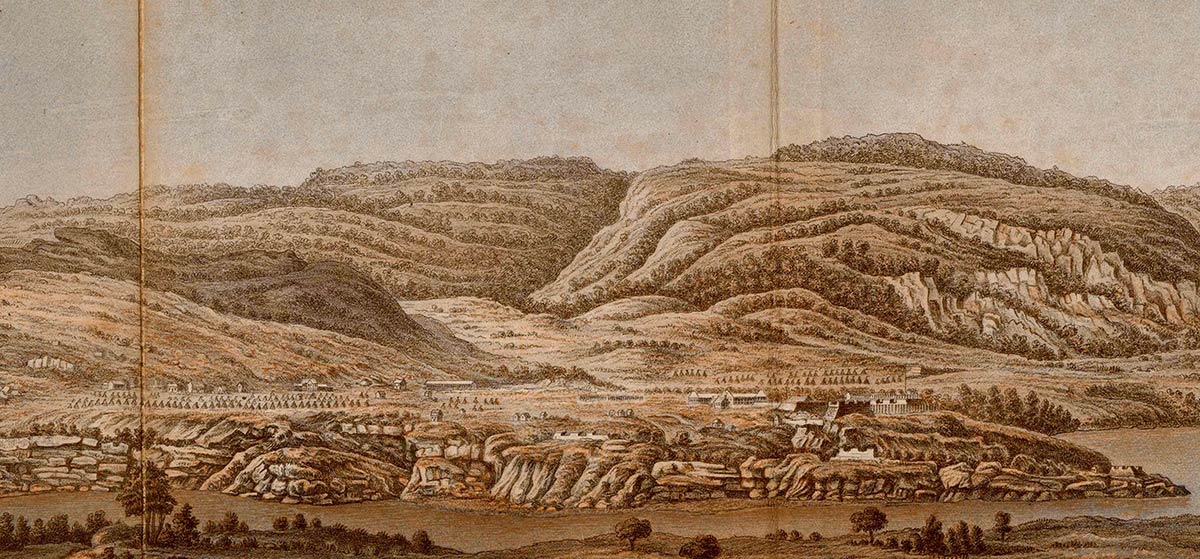

According to what USMA Department of Geography professors wrote in The Military Geography of Fortress West Point, “The geological structure of the Hudson Highlands lent logic to their fortifications…. Additionally, the highlands include characteristic fluvial and glacial terraces, about one hundred feet above sea level, one of which is the West Point Plain, and three remarkably sharp turns or angles in the river – at West Point, Anthony’s Nose, and Dunderberg – where the hard crystalline rock has withstood the erosive power of the water.” As can be seen in young French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s illustration of West Point completed in 1782, and commissioned by General Washington, the Plain eventually housed many structures including fortifications, tents, and various other buildings including barracks and a hospital. It was from here that troops assembled for the successful battle to recapture Stony Point from the British and from here that troops left to march to Yorktown.

It was on the Plain in the fall of 1780 that Baron von Steuben, a close friend of L’Enfant, trained the Continental soldiers in military maneuvers as he had at Valley Forge. As West Point historian LTG (Ret) Dave Palmer writes,”Men thrust and parried for hours. Arms and shoulders grew weary; muskets deemed to double and treble in weight. Yet at the grating sound of the German, the long knives snapped in unison, aimed thirstily at the jugular of an imaginary foeman.”

In October of 1780, Baron Von Steuben noticed that a young soldier from Connecticut had the last name Arnold and questioned him. Learning that he now hated his name, Von Steuben offered him his name. After the war was over, that soldier legally changed his name to Jonathan Arnold Steuben and Von Steuben and the farmer remained fast friends for life.

EXECUTION HOLLOW:

Execution Hollow can be seen in this photo of the Plain in the early 1900’s. There were two natural geological indentations or “kettles” on the Plain, both of which can be seen in the Cadet Yoakum drawing of 1832 above, the second located to the left of the remnants of Fort Clinton.

Filled in in the twentieth century, Execution Hollow can no longer be seen on The Plain in the location where it is purported that deserters were executed during the American Revolution.

Later it was used by the Military Academy to house Battery Byrne, a reinforced concrete, 12-inch coastal mortar battery with which cadets lobbed rounds into the side of Crow’s Nest Mountain. Recent construction at West Point has resulted in the discovery of several of these cannonballs in the vicinity of Keller Army Community Hospital.

Although not formally known as “The Plain” as it is today at West Point, the naturally occurring geography created the ideal cantonment and training area for Revolutionary soldiers. In 1778, First Lieutenant Samuel Richards, who as the senior officer present marched the 3rd Connecticut Regiment over the ice from Constitution Island to West Point on 27 January, recalled years later what the soldiers first saw: “Coming on to the small plain surrounded by high mountains, we found it covered with a growth of yellow pines ten or fifteen feet high; no house or improvement on it, the snow waist high. We fell to lopping down the tops of shrub pines and treading down the snow, spread our blankets, and lodged in that condition the first and second nights.”

According to what USMA Department of Geography professors wrote in The Military Geography of Fortress West Point, “The geological structure of the Hudson Highlands lent logic to their fortifications…. Additionally, the highlands include characteristic fluvial and glacial terraces, about one hundred feet above sea level, one of which is the West Point Plain, and three remarkably sharp turns or angles in the river – at West Point, Anthony’s Nose, and Dunderberg – where the hard crystalline rock has withstood the erosive power of the water.” As can be seen in young French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s illustration of West Point completed in 1782, and commissioned by General Washington, the Plain eventually housed many structures including fortifications, tents, and various other buildings including barracks and a hospital. It was from here that troops assembled for the successful battle to recapture Stony Point from the British and from here that troops left to march to Yorktown.

It was on the Plain in the fall of 1780 that Baron von Steuben, a close friend of L’Enfant, trained the Continental soldiers in military maneuvers as he had at Valley Forge. As West Point historian LTG (Ret) Dave Palmer writes,”Men thrust and parried for hours. Arms and shoulders grew weary; muskets deemed to double and treble in weight. Yet at the grating sound of the German, the long knives snapped in unison, aimed thirstily at the jugular of an imaginary foeman.”

In October of 1780, Baron Von Steuben noticed that a young soldier from Connecticut had the last name Arnold and questioned him. Learning that he now hated his name, Von Steuben offered him his name. After the war was over, that soldier legally changed his name to Jonathan Arnold Steuben and Von Steuben and the farmer remained fast friends for life.

Execution Hollow can be seen in this photo of the Plain in the early 1900’s. There were two natural geological indentations or “kettles” on the Plain, both of which can be seen in the Cadet Yoakum drawing of 1832 above, the second located to the left of the remnants of Fort Clinton.

Filled in in the twentieth century, Execution Hollow can no longer be seen on The Plain in the location where it is purported that deserters were executed during the American Revolution.

Later it was used by the Military Academy to house Battery Byrne, a reinforced concrete, 12-inch coastal mortar battery with which cadets lobbed rounds into the side of Crow’s Nest Mountain. Recent construction at West Point has resulted in the discovery of several of these cannonballs in the vicinity of Keller Army Community Hospital.